The arranged folksong is a bit like a precious stone, taken by a well-known composer and reset in a new setting, both creating an opportunity to view the well-known gem afresh, but also to create a new piece all-together. Benjamin Britten’s folksongs vary from simple re-arrangements to virtually brand new art-songs. I will be performing a selection of these in a programme called Sweeter than Roses, and other upcoming concerts.

Benjamin Britten

The first set was written during the self-imposed exile of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears – as conscientious objectors to the British War effort as well as the legal intolerance of homosexual partnerships – to the USA from 1932 to 1942. Published in 1943 these works therefore also reflect a certain nostalgia for the homeland of a composer in exile. Benjamin Britten (Lord Britten of Aldeburgh 1913-1976) needed recital and encore material for his recitals with England’s foremost tenor of the time, his life-partner Sir Peter Pears (1910-1986). By 1947, three sets of folksongs from the British Isles and mainland Europe were published, forming a treasure trove of recital material. Written with piano accompaniment, a few were orchestrated in the early 1950’s.

Folksong setting in Britain prior to Britten

Britten’s English folksong publication is predated by a massive project during the 1780’s by George Thomson Edinburgh (1757-1851), of publishing arrangements of folksongs by the greatest European composers. Thomson recruited no less than Joseph Haydn and Ludwig von Beethoven, Hummel and Carl Maria von Weber. The British public seemed to enjoy the prestige of these names, and there was an absolute boom in sales and interest in dressing up folkmusic in “civilised garb”.

Cecil Sharp (1859-1924) was another important figure in the history of English Folksong, collecting over 4000 folksongs and notating each by hand. He published 1, 118 folk melodies and wrote over 500 accompaniments. By all accounts he was not much of a composer, and his accompaniments and folksong settings are rather dull, but they are extremely valuable in the preservation of the vocal lines. According the Graham Johnson, veteran accompanist and close friend of Peter Pears in his last years, Cecil Sharp prided himself on the “unobtrusive” nature of his accompaniments, claiming that they added to the authenticity of his legacy.

Grainger's "Free Music Machine"

Australian pianist and composer Percy Grainger (1882-1961) came to Britain in 1901, using a recording machine. Britten got to know these recordings, conducting and recording “Salute to Percy Grainger” in the 1970’s for the Decca record Label. Grainger’s folksong transcriptions differ radically from his folksong arrangements, in that they are meticulously notated, often with highly complex metres and rhythmic patterns, as the young man strove to write down the performance he heard as accurately as possible.

Britten’s Folksongs

Britten was content to use the material collected by others. His songs are not meant for the ethnomusicologist or anthropologist. They are designed for a collector and analyst of a very different nature: the recitalist. Many writers have bemoaned the “artyness” of Britten’s folksong settings. They were specifically intended as encores and to end the Britten-Pears recitals.

Some musical characteristics of Britten’s folksong settings.

Britten was a great Schubert interpreter. The Britten/Pears Schöne Müllerin is a joy to hear. I am in awe of Britten’s control and fine sense of nuance in this performance in particular, but the entire Britten/Pears Schubert legacy is a treasure. As a performer, I sense something Schubertian in the folksong settings. As with some of Schubert’s accompaniments the piano parts are often based on a single motif or pianistic “idea” without too much development. The strophic nature of the songs lend themselves to a comparison with Die Schöne Müllerin . The beauty of the Britten settings is the simplicity but highly effective nature of the accompaniments, to reveal, introduce and weave the mood of the song. Britten’s experience as an opera composer comes into play in the more narrative songs, where dramatic scenes are spun with utmost efficiency.

I won’t be discussing all the folksongs in the settings here, but some that I am preparing for current concerts.

Down By The Salley Gardens (W. B Yeats) 1889

Down by the salley gardens my love and I did meet;

She passed the salley gardens with little snow-white feet.

She bid me take love easy, as the leaves grow on the tree;

But I, being young and foolish, with her did not agree.

In a field by the river my love and I did stand,

And on my leaning shoulder she laid her snow-white hand.

She bid me take life easy, as the grass grows on the weirs;

But I was young and foolish, and now am full of tears.

Salley Gardens where the lovers did meet

The Salley Gardens

Ironically, the first folksong isn’t really a folksong. Unhelpfully, Britten subtitles the song as “Irish Tune”. The text is by William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), Irish poet and dramatist and one of the greatest poets in the English language of the twentieth century. He was a leader of the “Irish Renaissance” and spiritualist, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923. It was published in 1889 in “The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems”.

Yeats indicated in a note that it was “an attempt to reconstruct an old song from three lines imperfectly remembered by an old peasant woman in the village of Ballisodare, Sligo, who often sings them to herself.” Yeats’s original title, “An Old Song Re-Sung”, reflected this; it first appeared under its present title when it was reprinted in Poems in 1895

The melody is by Northern Irish Composer Herbert Hughes, whose Down by the Sally Gardens was published in 1909 in “Irish Country Songs Vol. 1”, who originally used the text by Yeats. True, his accompaniment is clumsy and fussy, but he created the essence of the song. Britten’s “resetting” gives us the opportunity to appreciate the gem in all it’s glory.

All through The Sally Gardens the accompaniment suggests the slow falling of tears and – you will notice this at once when you hear the song – the introduction, at the start, of a note contradicting the key is a masterly touch. The gentle throb of the quaver pattern is broken by a sad little figure, but follows the natural rhythm of Yeats’ poem perfectly. A song both static and somehow “suspended” in time, a moment of reflection captured in space and time, this is a truly remarkable creation. A very effective “flattening” of the harmony on the final “young and foolish” is an expressive masterstroke of a composer acutely attuned to the mood and emotion of the text. The tiny postlude sums up the sadness of an older protagonist who remembers his/her own youth and the loss of love.

The Latin name for the Weeping Willow is the Salix, and willows are sometimes referred to in poetry as “weeping Salleys”. The Irish name for a willow is “Saileach”. “Salley Gardens” then could refer to a secluded willow grove where lover’s could tryst in secret and seclusion.

The Ashgrove – the version of the text set by Britten

Down yonder green valley where streamlets meander

When twilight is fading I pensively rove.

Or at the bright noontide in solitude wander

Amid the dark shades of the lonely ash grove.

Twas there while the blackbird was cheerfully singing

I first met that dear one, the joy of my heart.

Around us for gladness the bluebells were ringing

Ah! then little thought I how soon we should part.

Still glows the bright sunshine o’er valley and mountain,

Still warbles the blackbird its note from the tree;

Still trembles the moonbeam on streamlet and fountain,

But what are the beauties of Nature to me?

With sorrow, deep sorrow, my heart] is laden,

All day I go mourning in search of my love!

Ye echoes! oh tell me, where is the sweet maiden [loved one]?

“She [He] sleeps ‘neath the green turf down by the Ash Grove.”

Ashgrove in Winter

The Ashgrove

Subtitled “Welsh Tune”, the first published version of the tune was in 1802 in the book “The Bardic Museum” by harpist Edward Jones.. Telling of a sailor’s love of “Gwen of Lynn”, a similar tune appears in “The Beggar’s Opera” by John Gay (1728) in the song “Cease your Funning.”

Britten here moves away from simple “Folksong setting” or Schubertian “artistry”, experimenting with harmonies and canons and passages in varied imitation. The bluebells “chime” almost literally in the piano part. A little Messianic bluebird triplet ruffles the feathers of traditional folksong collectors and various harmonic shifts, reflect an unstable mind. The simple tune belies the tragedy of the text, and Britten’s miniature mad-scene is filled with tremendous empathy for the suffering of the mourning lover.

O Waly, Waly – The text as set by Britten

The water is wide, I cannot cross o’er,

But Neither have I the wings to fly.

Give me a boat, that can carry two,

And both shall row, my love and I.

I leaned my back up against an oak

I thought it was a trusty tree

but first it bent and then it broke

And so my love did unto me.

A ship there is and she sails the sea,

She’s loaded deep as deep can be,

But not so deep as the love I’m in

I know not if I sink or swim.

O love is handsome and love is fine

And love’s a jewel when it is new

but love grows old and waxes cold

And fades away like morning dew.

The inherent challenges of love are made apparent in the narrator’s imagery: “Love is handsome, love is kind” during the novel honeymoon phase of any relationship. However, as time progresses, “love grows old, and waxes cold”. Even true love, the narrator admits, can “fade away like morning dew”

Britten here uses the tune as transcribed by Cecil Sharp on his trip to America during World War 1. It is thought to be a Scottish or English Folksong. Britten creates a sparse accompaniment allowing the voice to float free. A gentle barcarolle rhythm in the accompaniment sets the watery scene that rocks with a gentle ebb and flow. The harmonies in the accompany change, but very slowly, gently. The subtle changes makes this song a hypnotic masterpiece. Powerful but understated discords such as the one on the word “cold” create new meanings in the text. In one chord, the disintegration of a relationship is expressed, summed up, wrapped up in a flattened seventh at once comforting as symbolic of the death of love.

Down By The Salley Gardens: Some Recorded Materials

Tenor John McCormack performing an arrangement not by Britten. I enjoy his “folk” accent and the glimpse into the past provided by the scratchiness of the old record.

Countertenor Andreas Scholl performing (in the studio in 2001) an arrangement for voice and string orchestra. While the strings add the rustling of the trees of the “Salley Gardens” I do miss the simplicity of Britten.

Nicolai Gedda and Gerald Moore, another great Schubertian pianist, give a rather “recitalish” performance. However, Gedda, whose range of recording and performance simply continues to amaze me for its sheer breadth and depth, displays admirable sensitiveity to the text.

Irish folk duo Lark and Spur sing a charming popular celtic version.

The Ashgrove: Some Recorded Materials

Nana Mouskouri with two guitarists accompanying.

These original Welsh words tell a violent, bitter tale. A young heiress falls in love, to the dismay and rage of her powerful father and lord of the region. He means to kill her lover, but kills her by chance, and she prefers death to being an unloved prisoner at Ash Grove Palace. It is sung here in Welsh by Llwyn Onn as Dafydd o Fargoed. The accompaniment is based on Benjamin Britten’s arrangement from 1943 set then to gentle English words of mourning for a dead lover.

O Waly, Waly: Some Recorded Materials

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears give the autoratitive version. The pathos and pianissimo of the final verse is breathtaking.

A modern tenor version by American tenor Gregory Kunde. The pianist is not credited in this live 1998 perfromance.

Sir Thomas Allen sings an unaccompanied version at the Northumbrian seashore. The seagulls in the background form a touching accompaniment to a tune of great power.

At the other end of the spectrum is Bob Dylan in a live 1975 version.

The beautiful and always sensitive Eva Cassidy sings a touching version I would not want to be without.

The Foggy, Foggy Dew: Some Recorded Materials

Tenor Steve Davislim and pianist Simone Young perform the Britten arrangement of folksong ‘Foggy, Foggy Dew’ and speak about thier approach to presenting this piece. From ‘Benjamin Britten Folksong Arrangements’, MR301120 Melba Recordings SACD.

Sinead O’Connor and the Chieftains sing the Irish republican song “The Foggy Dew”.

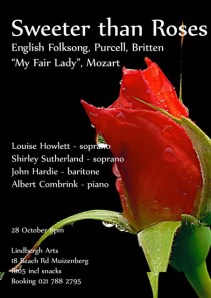

I will be performing these and other Britten folksong settings in concerts over the next few months. One of these features singers Louise Howlett, Shirley Sutherland and John Hardie, accompanied by Albert Combrink. Also on the programme is “Sweeter than roses” and other Britten realisations of Purcell songs, and extracts from that delightful Rose seller Eliza Doolitle from “My Fair Lady”, and some operatic roses such the one one Carmen throws at at Jose, intoxicated with love.

Thank you Albert – completely fascinating as always