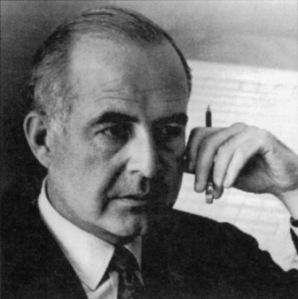

American Composer Samuel Barber

I am preparing a group of recitals of American Art-songs with American soprano Judith Kellock, which will include a selection of songs by Samuel Barber (1910-1982). The challenge for the pianist is, of course, the difficult piano writing. As Judith Kellock and I have not yet rehearsed our recital programme, I can not comment on the symbiosis between singer and accompanist in these songs. But it is a recital for which I can’t wait. Judith Kellock’s recording of Barber Songs has been highly acclaimed and I am looking forward to performing these songs with her in Cape Town and Port Elizabeth in August 2009.

Barber is known for the famous “Adagio for Strings”, in its original form for String quartet, arranged by Barber for String Orchestra or re-shaped as a choral “Agnus Dei”. This work sums up many aspects of Barber’s compositional style: the quintessential “American Elegy”, going directly to the heart of the matter, a powerful and soaring melody and a lush texture with which to support its emotional charge. These elements are found in most of Barber’s works, including his impressive body of vocal works. Barber’s songs have become synoymous with the American Art song, attaining the status of American classics. He wrote songs throughout his life, starting in his teens. At 14, he was enrolled into the newly formed Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and a year later, his first known song, “A Slumber song to the Madonna” appeared. At 17 “The Daisies” became his first published song. His last song for solo voice and piano, “O Boundless, Boundless Evening” was written in 1972.

He wrote less prolifically in his last twenty years, but he was busy with vocal music throughout his career. Over 50 songs appear between other vocal works.

His affinity for the voice is clear. Consider operas “Vanessa” and “Anthony and Cleopatra”, along with many other vocal works many scenas, cantatas and works such as “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” (set to a text by James Agee). He also maintained close relationships with singers thoughout his life. His aunt, the opera singer Louise Homer, gave many of the first performances of his songs. Pierre Bernac and Francis Poulenc were friends and supporters as well as performers of his works. And at a time when large parts of the American music world was still segregated, he supported careers of young black singers such as Leontyne Price and Martina Arroyo.

Barber’s music has been described as “Neo-Romantic”. He uses a contemporary harmonic and rhythmic language, but there is always a warm melodic content. His music is perhaps less “American” than, say, Copland, but then it is also less forbidding. There is always a deep passion in his writing. His seriousness as a person was overlaid with a witty mien, which his good friend and publisher Paul Wittke describes as “a defence against a deep-rooted melancholia.” Pianist John Browning – a great interpreter of Barber – writes most beautifully: “Barber’s language is that of the poet – swift changes of mood and a pervading melancholy and loneliness conveyed on a sumptuous harmonic tapestry. There is a passionate sensuality which never lapses into cheap sentimentality or vulgarity” (Barber: The Songs, DGG CD Booklet, p10)

“Barberisms” include: • Rich orchestration and harmonies reminiscent of late romantic composers such as Rachmaninov or Strauss. • A solid grasp of polyphony. • Easy chromaticism that remains within a tonal framework. • A lush lyrical gift.

All his works contain memorable melodies. These elements fuse in his vocal works. Barber himself had many skills to contribute as an art-song composer. He was an excellent singer himself, having studied singing with Emilio de Gogorza and later in Vienna. He even flirted with a professional singing career, performing and recording as a singer, including the first recording in 1935 of “Dover Beach” for Baritone and String Quartet, a sophisticated work composed when Barber was just 21– and a beautiful performance it is. An excellent pianist, Barber studied with Russian pedagogue Isabelle Vengerova. Barber’s writing for the instrument is some of the most complex and virtuosic of the 20th Century. His Piano Concerto (premiered 1962) remains an Everest of piano technique and the Piano Sonata is considered one of the most challenging ever written. The Sonata was first performed by one of the great virtuosos Vladimir Horowitz. Here you can follow the score as you listen to the recording. The Fugue is famous for it’s demands. His songs make few concessions. Richly contrapuntal writing and filigree passages make his accompaniments a challenge and a feast for pianists.

Comfortable in various languages, Barber’s song-texts are of the highest quality. He read poetry in its original language (he was fluent in Italian, German and French) and almost never went anywhere without a volume of poetry within reach. Yet he claims to have had difficulty chosing poems, finding some to wordy or too introverted, and he always appeared to be reading poetry with an eye to it’s potential as compositional material.

Some thoughts on songs in the recital:

A Nun takes the Veil – Op.13, No.1 (Gerald Manley Hopkins) 1937

Schubertian in its purity, this song conjures up a young woman’s vision of the sanctity of a monastery. Harp-like broken chords alternate with hymnal solemnity to create a vision of spiritual ecstasy. Judith Kellock’s interpretation captures a wonderful intimate atmosphere .

The Secrets of the Old – Op.13, No.2 (W.B. Yeats) 1938

A Celtic folk-tale is conjured up in a quirky rhythm in odd-metres. It is a lovely combination of old-fashioned story-telling, the irony of which is made more poignant by the trademark harmonic bite. The bittersweet melody and contrapuntal textures reflect the new direction Barber’s music was taking after he spent two years living and travelling in Europe.

Sure on this shining night – Op.13, No.1 (James Agee) 1938

One of the greatest songs of the 20th Century, this song reminds of Robert Schumann in that the melody is echoed in a piano melody and supported by repeated chords. It has been recorded often, arranged as a choral work, and orchestrated by Barber. I enjoyed hearing Julia Metzler’s performance And of course Cheryl Studer in the now famous DGG recording of the complete songs.

Nocturne – Op.13, No.4 (Frederic Prokosch) 1940

This is another song with rich and luminous textures which lent itself to orchestration. Conjuring up the magic of night, the melody encompasses broad leaps, and some surprisingly angular intervals that become achingly tender when supported on waves of rich harmony. Despite many chromatic excursions, tonality is never abandoned and the piano filigree ripples through the water-imagery with Debussian delicacy. This song is hauntingly beautiful, and exemplary of Barberian melancholy.

The Queen’s face on the summery coin Op.18, No.1 (Robert Horan) 1942

A much more complex Barber is encountered here. Written in the year of his “Second Essay for Orchestra” which the composer said himself reflected “that it was written in wartime”, the work uses canon and modal elements to create a work which does sit as uneasily on the heart as it does on the ear, stuck between a minor and diminished chord resolution.

Monks and Raisins Op.18, No.2 (Jose Garcia Villa) 1943

The quirky 7/8 rhythm is a perfect vehicle for this comic tale of pink monks eating blue raisins and blue monks eating pink raisins. By the time the storyteller eats both colours together one’s head is spinning with “the blue and the pink counterpointing”!

Nuvoletta Op. 25 (James Joyce) 1947

Joyce’s method of stream of consciousness, literary allusions and free dream associations was pushed to the limit in some of his works such as “Finnegan’s Wake”. Barber seems to follow the text in the same manner of free association and with a tongue-in-cheek- flutter of Nuvoletta’s light dress, the music disappears, and one is left trying to make sense of the recollections. Barber claimed in a radio interview that he included a few ironic quotes from Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde”. I am still learning this piece, and therefore I am still on the look-out for said quotation!

The recitals with Judith Kellock will include “Try me Good King”, a cycle by Libby Larsen, as well as “Four American Songs” by South African composer Peter Louis van Dijk.

Judith Kellock's CD of Barber Songs

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.