Puccini’s private life seems to be a good subject for a soap opera. He appears to have been happily married to a good wife who was not a big music fan, but nonetheless supported him and his career for his whole life. She also had patience with a husband who entertained a number of extra-marital relations with women from all social circles. Much has been said already on the overlaps in context of Puccini’s leading ladies, both on- and offstage. In comparison with the detailed psychological exploration of his female characters, the men seem rather a more straightforward band of conventional villains, heroes and poetic lovers.

Women in Puccini’s operas have been the butt of many jokes. They seem to epitomise the worst aspects of opera. Mimi in La Boheme, while dying of consumption, nevertheless remains in good enough health to sing her way through a 20 minute death scene. The slave girl Liu stabs herself to avoid giving away the true identity of her beloved, to save his life from the icy princess Turandot. Sister Angelica drinks poison out of guilt at having been in a convent while her child died far away.

Tosca stabs the evil Baron Scarpia, killing him violently. To avoid arrest for his murder, she flings herself off the parapet of the Castello Saint Angelo. In the theatre one hopes that she lands on the mattress placed below. In some productions – and even more urban legends – the diva occasionally misses the bulls-eye. Or even bounces back into full view of the audience.The Japanese Madama Butterfly commits Hari Kiri with the same knife with which her father killed himself to restore honour to the family after an incident of shame. That is a lot of self-inflicted bleeding.

Yet these murders, suicides and “unhappy endings” go right to the hearts of audiences. Even in a rehearsal of La Boheme, I have seen cast and bystanders in tears at the pathos and unbearable beauty of Mimi’s last desperate love for the poet Rodolfo, and even the flighty character of Musetta responds with a depth of emotion that touches the heart. As Liu grabs her torturer’s knife and plunges it into her heart and the chorus yells “Parla! Parla!” (Speak! Speak!) the audience reacts with the same – but silent – scream.

When the American soldier Pinkerton comes rushing onstage, yelling “Butterfly! Butterfly!” as the blood and life seeps out of her self-inflicted stab-wound, the audience is also yelling a silent “Butterfly! Butterfly!” and gasping at the tragedy.

Of course, the key to all this screaming and bleeding is the exquisite music. Somehow one looks past the incongruities. A healthy, robust, Top-C-Singing soprano playing the role of a young girl, wasted away by terminal TB? A 50 year old Italian dramatic soprano who plays a 16 year old Japanese teenage mother? A massive Tosca the object of lust and desire? All is presented in multiple layers of aural meaning.

Puccini was a master at orchestration and melody, and he had an unerring sense of drama. The so-called “arias” and duets” in his operas are rarely stand-alone items, but they are built into the fabric of the drama at appropriate moments. Some even consider the lack of “applause breaks” to be a weakness in Puccini’s operas. In certain cases, conventions have developed whereby the written music is altered to create “applause moments”. It can create chaos when the audience roars its approval while the conductor and the stage-party attempt to continue. Tosca’s Visi d’arte provides a moment’s respite from all the histrionics that preceded it and the murder and attempted rape that races the act to its climax. Musetta’s waltz Quando m’en vo’ – basically a “concert-number” (an excuse for an aria) – is a break in the hustle and bustle of the Café-scene and acts as the dramatic foil for the deeper and more serious elements of the love-story of the Bohemians. And this is often the main complaint against Puccini’s arias: that they tend to hold up the drama rather than move it forward.

Some of us don’t really mind. They make some of the most glorious moments in all of opera.

One such moment is the Duet Tutti i fior, from Madame Butterfly. Cio-cio San, the beautiful but fragile and short-lived heroine of the title, has been waiting anxiously for news of the return of her American soldier husband whom she married earlier in the opera. In her naïve youth and the flush of first love, she believed his promise to send for her on his return to America. She rejected her ancestral religion and converted to Christianity for Pinkerton’s sake and insisted that she was no longer to be called Madama Butterfly, but Madama Pinkerton instead. Pinkerton meanwhile viewed the whole experience as the colonial prerogative of a young navy officer at sea, intending to find a Butterfly in every port. Bridal contracts and house rental, according to him are done the “Japanese Way”: 999 year lease with a month-by month-option to cancel. Yet, it seems this was more the American way: back in the USA he found himself a proper American bride and had no intention of ever seeing Butterfly again.

At last – after three years of waiting – Butterfly’s prayers are answered. Her faithfulness is rewarded with a canon-shot from the harbor, announcing the arrival of the Abraham Lincoln, Lieutenant Pinkerton’s ship. What follows is one of the most exquisite scenes in the opera. An ecstatic Butterfly and her faithful maid Suzuki shake the cherry-trees in her garden, picking up the soft rain of petals. They decorate the house with flowers from her garden, strewing them everywhere, even twining them around a chair especially placed for the return of the conquering hero. “Everywhere must be full of flowers”, Butterfly sings. “As full of flowers as the night is full of stars”. As their aroma fills the house, Butterfly, in anticipation of her second wedding night with her returning husband, puts on her most exquisite make-up and even dons her wedding dress.

I gave tears to the soil. It gives its flowers to me.

The bitter-sweetness of this moment is presented in exquisitely lyric poetry and music. Butterfly’s love and naivety are clearly audible. Her excitement at the thought of shortly seeing Pinkerton is illustrated by the nervous key-changes and scurrying passages. Her sadness is underlined by darker harmonies. When she sings in anticipation of the happiness of reunion, the music soars in timeless suspended ecstasy. Suzuki, perhaps the older and wiser of the two women, keeps reminding Butterfly that stripping all the flowers from the garden would leave it bare, as winter. Butterfly is almost foolhardy in her insistence that they “bring spring inside”. Her obsessive recreation of the spring of their marriage is also a desperate attempt to console herself for the agony of the past three years. Pinkerton also uses nature imagery early in the opera when he admits that he will “play with the butterfly even if doing so will damage its wings”.

Amidst the glory and beauty of the music, and the intoxication of the scent, there is already a foreshadowing of the tragic death. In much the same way, the canon-shot which announces the arrival of Pinkerton’s ship, is symbolic of the “shot to the heart” Butterfly will receive when she can no longer deceive herself and grasps the truth. The beauty of the duet is even more poignant, as by now, the audience knows the end of the story. Even the dagger with which she will do the deed, is introduced early in the opera. Butterfly’s father had been instructed to kill himself with that exact dagger. Butterfly kills herself so that her child by Pinkerton can start a new life in America. The harmonic tensions in the passage where she send her child from the room to go and play while she kills herself, is unbearably emotional. Butterfly arouses endless pity and sympathy.

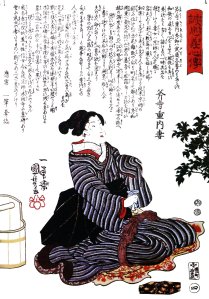

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川国芳) (1797 – 1861) – “Onodera Junai’s Seppuku”

The reality of Hari Kiri (also known as Seppuku) was far more cruel than encountered in the orientalist romance of the opera stage. This painting depicts Onodera Junai (wife of a samurai) preparing for jigai (female version of seppuku) to follow her husband in death. Her legs are bound as to maintain a decent posture in agony. Death is given by a tanto cut at the jugular vein. This woodcut by Utagawa Kuniyoshi is from a series called Seichu gishin den, (“Story of truthful hearts”), 1848. This series is based on a true story of 47 Ronen or Samurai who had to commit Hari Kiri for having committed murder to revenge the death of their master. The story was popularized in Japanese culture as emblematic of the loyalty, sacrifice, persistence, and honour that all good people should preserve in their daily lives. To me, this example of the force of loyalty and devotion, identifies Butterfly’s suicide as the ultimate gesture of fidelity to Pinkerton and, by implication, their son.

Butterfly as Geisha

For two brief but insightful and fascinating views on the life and work-expectations of the Geisha – the work Butterfly did before her marriage – I refer you to the following excellent sites:

– Geisha Study Guide (Pacific Opera, Victoria, Canada)

– The Geisha (Okinawa Soba)

Japonisms in the “Flower Duet” – Puccini’s use of Japanese Folksongs in Madama Butterfly

Puccini definitely used some Japanese folk melodies in the score of Madama Butterfly. Tom Potter’s excellent 2006 article Japanese Songs in Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly contains sheet music and audio files of songs and where they happen in the score. None of these appear to have been used in the Flower Duet. As with large chunks of Turandot – Puccini’s other orientalist opera set in Peking – here it is clear that we are listening to a full-blooded romantic Italian composer at work. The freedom of the harmonies, the expressive fluctuations in tempo, and above all the exquisiteness of the vocal line, are all original Puccini at his best.

Viva Italia!

Beverley Chiat and Violina Angeulov will be performing the Flower Duet in various upcoming performances. You can read more about the performers and other works on the programme by clicking on the following links:

– Beverley the Beautiful Butterfly

– Violina Angeulov performing Durante’s “Danza, danza fanciulla”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.